Of the two great autocratic powers in Eurasia, Russia is emerging as a greater short-term threat than China. The Chinese hope to gradually dominate the waters off the Asian mainland without getting into a shooting war with the U.S. Yet while Beijing’s aggression is cool, Moscow’s is hot. When the current U.S. administration seems out of gas and a new one is not in place, there has never been a better opportunity for Russian President Vladimir Putin to veer toward brinkmanship.

Russia’s economic situation is much worse than China’s, and so the incentive of its leaders to dial up nationalism is that much greater. But the larger factor, one that Western elites have trouble understanding, cannot be quantified: A deeply embedded sense of historical insecurity makes Russian aggression crude, brazen, bloodthirsty and risk-prone. While the Chinese build runways on disputed islands and send fishing fleets into disputed waters, the Russians send thugs with ski masks into Ukraine and drop cluster bombs on unarmed civilians in Aleppo, Syria.

Not counting the cyber domain, where its interference in our politics is approaching an act of war, Russia is engaged in aggression in four theaters: the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea basin, Ukraine and Syria. Yet to Moscow this constitutes one theater—the Russian “near abroad” that includes the periphery of the old Soviet Union and its shadow zones of influence. Because Mr. Putin sees this as one fluid Eurasian theater, if the U.S. were to put pressure on him in Syria, say, he could easily respond in the Baltic states.

Such a reaction would be designed to split the Western alliance. Consider a scenario that came up during a war-game I participated in last winter in Washington: Russia could send only a few hundred uniformed troops a few miles inside one of the Baltic states and then stop.

It would be daring NATO to escalate by declaring an Article 5 violation—in which an attack on one ally is an attack on all. Mr. Putin knows that the NATO members in southern Europe, Greece, Bulgaria and Italy, might hesitate to support an intervention, even while Russian troops vastly outnumber NATO soldiers in the Baltic region. By the time NATO deployed sufficient strength, Russia could overrun one of the Baltic NATO members.

As for the role of Syria: In 2011 the U.S. might have had strategic opportunities there had the White House acted. A half-decade later, the opportunities have narrowed and the risks have intensified. One precedent that has been invoked is the siege of Sarajevo in the 1990s, which helped lead to a Western military intervention. But then President Bill Clinton came up against a weak Russia, no competing outside powers and no indigenous fighters who were international terrorists.

The U.S. may be able to relieve the suffering in Aleppo, and military experts can advance that argument. But keep in mind there is a vast distance between making predatory aggression much harder for the Syrian regime in the northern part of the country (doable) and toppling that regime in Damascus (too ambitious at this point).

There is also a larger foreign-policy question that must be the first order of business for the new president: How does the U.S. build leverage on the ground, from the Baltic Sea to the Syrian desert, that puts America in a position where negotiations with Russia can make a strategic difference?

For without the proper geopolitical context, the secretary of state is a missionary, not a diplomat. Secretary of State John Kerry is a man who has a checklist of negotiations he wants to conduct rather than a checklist of American interests he wants to defend. He doesn’t seem to realize that interests come before values in foreign policy; only if the former are understood do the latter have weight.

For example, just as Western military intervention in Syria risks a Russian response in Europe, a robust movement of American forces permanently back to Europe may cause Mr. Putin to be more reasonable in Syria. This may offer a way out of the sterile Syria debate, in which all the options—from establishing safe zones to toppling Bashar Assad’s regime—are problematic and offer no end to the war. By seriously pressuring Russia in Eastern and Central Europe, the U.S. can create conditions for a meaningful negotiation whereby Moscow might have an incentive to shape the behavior of its Syrian client in a better direction.

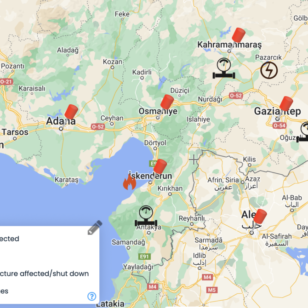

Because the Syrian conflict is a regional war, the other powers—Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran—would have to be involved. Here, too, American diplomacy can be meaningful only if the U.S. can better reassure its Middle Eastern allies with, for example, a more-robust deployment of military assets, from special-forces trainers to warships in the Eastern Mediterranean and Persian Gulf. Even ending sequestration would help in this regard—anything that provides a better context for projecting power. Diplomacy is not a replacement for force, but its accompaniment. At root, this is what separates presidents like Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan from Barack Obama.

In the cyber domain the U.S. has not sufficiently drawn red lines. What kind of Russian hacking will result in either a proportionate, or even disproportionate, punitive response? The Obama administration seems to be proceeding ad hoc, as it has done with Russia policy in general. The next administration, along with projecting military force throughout the Russian near abroad, will have to project force in cyberspace, too.

I am a realist—and realism dictates that Russia’s aggression in its near abroad has upset the balance of power and has for some time required a definitive response. The fact that President Obama has been wary of quagmires is merely a tactic. It does not give him an overarching philosophy or make him a realist. That is where the problem lies in Syria and elsewhere.

Initially published by Wall Street Journal.