The corona crisis made the oil price war led by the largest oil exporter (KSA) unprofitable for everyone. With no adjustments made, the oil price would have probably dropped fast to reach zero dollars or below hitting hard all world producers. With the current adjustments, considering the OPEC+ deal agreed upon on April 12 looks to reduce oil output by 9.7 mil bpd, the oil price just drops at a slower pace. But the new agreement doesn’t mean the price war has stopped – it has just moved on to Eurasia, affecting the American economy less than before.

Oil demand considerations

The oil demand is inelastic – meaning the quantity bought doesn’t change much when the price does. In other words, no matter the price, you need energy. In the same time, small changes of demanded quantity drive sudden (and sometimes dramatic) changes in price. That is no news to anyone – it is the rule.

China lockdown in February caused a decrease in demand by 1.8 mbd year-on-year while global demand was down by 2.5 mb/d during the first quarter of 2020, according to the IEA. According to the same source, Covid-19 crisis is supposed to produce a decrease in demand that goes to 2009 crisis levels – assuming that demand goes back up, to normal levels, during the second half of 2020.

However, forecasts on what happens on the oil market are really guesses at the moment – we don’t have precise data to show what’s the full impact of the current crisis and therefore uncertainty is included in all forecasts made. What we know is that demand contracted already by 35% – if we consider the 100 mil bpd production levels before the crisis, the drop takes 35 mil bpd out of the market. We also know that the supply chains were most influenced by the current crisis and that transportation dropped dramatically due to imposed quarantines all over Europe and the U.S. – key world consumers.

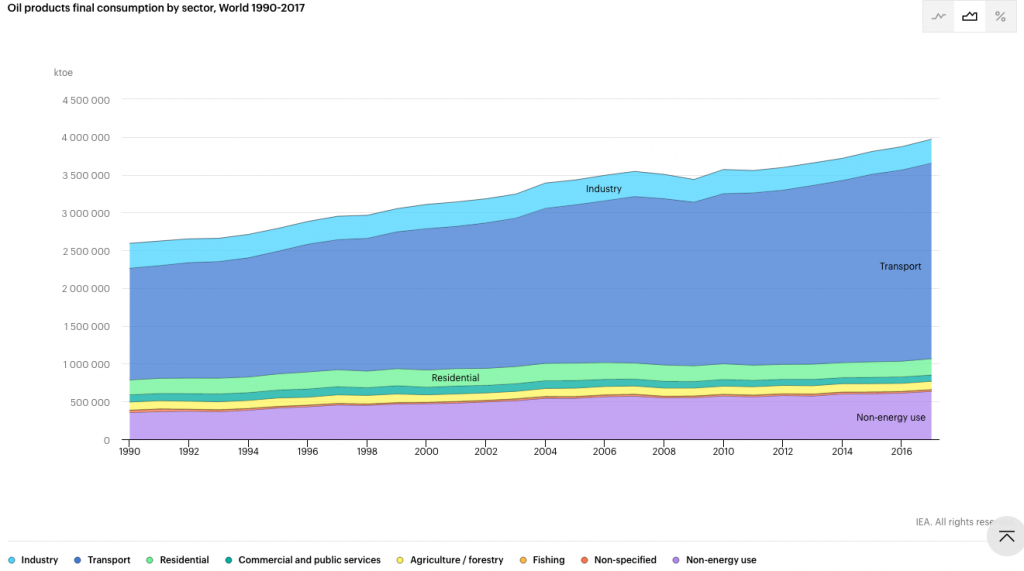

The transportation sector development (based on the increased complexity of the global supply chains) is what have kept oil demand growing during the last decade. With corona crisis, people have stayed indoors while businesses were partially shut down. If the close-down of activities had lasted for weeks or, better, if we had known how much it would last, the impact of the current could have been calculated and risks assumed, forecasts could be made. But that hasn’t been and is not the case.

source: EIA

In times of less uncertainty, when contractions could be calculated, OPEC has often chosen to micromanage the oil market, by subtracting small supply quantities. But never before changes occurred on multi-month time-frame (with no end in sight for the big consumers) and never before had changes in demand been more than a couple million barrels – now we’re talking a drop in demand from 15 to 35 million barrels over the quarter, with the bulk of it happening during the last 3 weeks when the U.S. entered quarantine measures (transport fuels account for about two-thirds of US oil demand).

Supply considerations

The OPEC deal agreed upon on April 12 looks to reduce oil output by 9.7 mil bpd. This is obviously too little to bring supply in line with demand, considering the above. But it helps save face value for all key political players in uncertain times.

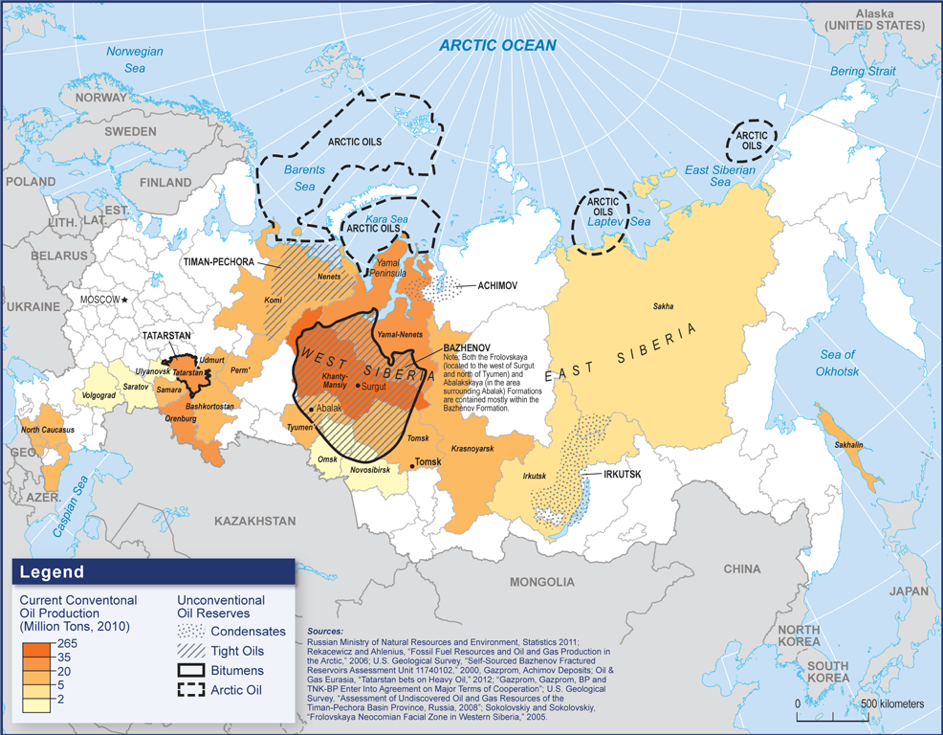

The idea of an agreement dates back in February. When the coronavirus epidemic reduced Chinese demand, the Saudis realized that if there was no broad alliance to reduce output, the oil price was about to drop fast. Everyone signed on to the idea, except the Russians who had plans to bring more production to the market and, considering the reported absence of a corona epidemic in Russia at the time, had no political incentive to agree. Plus, Russia has its own reality: due to climatic and geologic conditions, Russia couldn’t ever really reduce output. The most it can do is claiming to cooperate and, in times of need, include some extra seasonal maintenance while benefiting the Saudi reductions.

Saudi Arabia knows this well, but with no claim of cooperation obtained from Moscow, the world’s largest oil exporter launched a price war. In an aggressive manner, Riyadh started bringing their spare production on-line to see just how much oil they could dump on the market. That effort caused their exports to grow by over 1mbpd during March. Increasing pressure on the oil market, during the same time that the effects of the corona crisis were unravelling the world, worked to bring all oil producers back to the negotiation table – with the U.S. pushing for an agreement, in an unprecedented move.

source: Carnegie Endowment

In March, things have changed rapidly for Russia, too. Quarantine is imposed in Moscow and other major cities and the corona crisis had to be admitted. But, more importantly, Covid-19 has hit the U.S. and Europe. For Russia, Europe is the most important energy market. The complex relation Russia currently has with the U.S. is currently reduced to a simple fact: Russia holds about $560 billion dollars in financial reserves. But most of the reserve is not in US dollars, so its value will rapidly drop in value, considering the crisis will likely make the dollar the only thing growing in value, while everything else will be dropping. Realizing this, along with the potential impact of the corona crisis on European and national economy, made Moscow – and Putin in particular reconsider its decision on the OPEC agreement. The last thing he wants is to be found guilty of economic mismanagement – if reserves drop in value and Russians have to suffer, it has to be someone else’s fault and not Moscow’s.

In the U.S. the covid-19 also started to hit hard in late March. President Trump, facing a re-election campaign and a plunging economy this year, considering the American shale oil companies were already struggling with the dropping prices, made the agreement a priority. Moreover, the U.S. got additional help from the Saudis. On April 13, Riyadh announced that they added a $5 to the price per barrel of crude shipped to the U.S., while cutting the price for Asian deliveries. That means that the Saudis will stop dumping crude oil on the U.S. market and therefore the shale producers will not go out of business soon.

Storage & the ongoing price war

Saudi announcement on price differentiation between American and Asian markets means that Riyadh will intensify its price war in Eurasia. Whatever quantity of supply that is not sent to the Gulf of Mexico will be sent to Asia, where the KSA competes with Russia (and Iran, Nigeria or Iraq, but to a lesser extent). While Riyadh knows Russia will break the agreement – as it has done it before, it also knows it has little time to gain profits.

While there the world storage capacity level isn’t known with certainty, it is estimated to be between 0.9-1.8 billion barrels. That is equal to 9-18 days of global supply of 100 million bpd (or between 90-180 to accommodate supply exceeding demand by 10 bpd or 10%). Reports about Caribbean storage and the storage at Cushing in the United States nearing capacity and the math on demand and supply points to the fact that the world may be soon running out of storage capacity. Saudi Arabia, as Russia and as any other oil producer is interested to sell the most until that happens. That’s when the price comes close, may touch and go beyond zero if the corona crisis doesn’t stop and if the world is still in quarantine.

Considering the average of 1.35 billion barrels for world storage capacity and taking that all oil producers will stick to the OPEC plan recently agreed upon, then all capacity will be filled by early June (67 days). If the current deal collapses with everyone pumping in the market, the zero oil price will likely be registered earlier, in mid-May. Ultimately, the outlook for the oil price depends on how quickly the coronavirus outbreak is contained, how fast people get out of the imposed isolation regimes and what the impact of the current health crisis is on the economic activity.