The Black Sea Region is a global node of trade and traffic. While we usually check the power play in the borderlands to understand the features of the region and indicate the sources for new risks, considering hybrid warfare characteristics, this method becomes obsolete when global events strike – therefore, we must turn to the nodes. An analysis of the maritime traffic in the Black Sea node, while also considering those patterns related to regional security may tell of initial challenges that the region will face post the current pandemic. Such an approach also concludes on potential regional trends, considering the fluid borderline environment.

The Patterns

With the consequences of the 2008 economic crisis spreading during the last decade into the social and political areas of society, nationalism and populism grew all over the world. In essence, while the global environment remained peaceful, it wasn’t stable anymore. In 2008, it became clear that globalization was deepening the differences between classes and countries, depending on the level of the value chain these were finding themselves.

The role of the U.S. in the world was challenged by the socio-economic problems the U.S. was facing internally. In the same time, as China was working to remodel their socio-economic system and diminish its dependency on the U.S. markets, the infrastructure projects to Europe, all part of the New Silk Road Strategy were meeting resistance from the very realities of the market it was seeking to enter: the EU was dealing with a period of economic decline itself.

The Russian economy had first experienced a decline and stagnant growth due to the global economic crisis and later it saw the decline and slow growth deepening as a result of the U.S. and European sanctions. Internal resilience was partly supported by the growing nationalism and the idea that Russia had become again powerful, at the global level. In fact, to maintain internal support, Kremlin has been working to keep the U.S. engaged in the Middle East by supporting the Assad regime in the Syrian conflict, which essentially transformed into a regional challenge.

Consequently, the E.U., already troubled by socio-economic effects of the 2008 crisis, had to manage a refugee crisis. In 2015-2016, an increasing number of persons were fleeing the Syrian war in the hope of a better life in Europe, competing with others fleeing other countries of the Middle East or North African conflict zones or simply put, harsh societies.

The refugees and migrants have been choosing among several routes to go to Western Europe, the region that was seen as the best to make a better living. One of them was the Balkan route, which starts in Turkey. As a country directly involved in the Syrian conflict, considering its strategic interest in the region, which was also directly linked to its internal stability considering the implications for the country’s Kurdish minority, Turkey’s negotiation power with the EU has grown as the refugee crisis started. More importantly, its regional balancing act between Russia and the U.S. points to its recently announced neo-Ottoman policy, which seeks to re-establish Turkey as a regional power.

This confirms, for the Black Sea region, not only the potential for strategic re-alignment, but also a changing security and socio-economic environment. The NATO ally, which likely needs to remain the U.S. ally, will, whenever needed, meet Russia’s interests. In the same time, the U.S., who is seeking a way out of the Middle East, while remaining engaged on the Eastern Flank, will look to keep costs at a minimum. Considering the Eastern Flank current composition, with troops on the new containment line from the Baltic to the Black Sea, it is not all NATO allies but only some that participate in the new Intermarium – and Turkey is not one of them.

All of the above paint the dilution of the post-Cold War era. Old alliances like NATO and the EU, initially reformed, need to be reinvented, as countries increasingly seek their realistic, national imperatives, out of the globalization framed realities of trade and investment. The stability of the Black Sea area, as that of other areas of the Globe that are naturally nodal, is being challenged.

The pandemic

The covid-19 pandemic underlined the need for restructuring, forcing countries all over the world to look inwards and investigate dependencies over other states. The corona crisis that hit the Globe has exposed the global supply chain, showing, once more, the vulnerabilities of globalization. In the same time, however, it has also featured the benefits of digitization and the internet, underlining the differences between the urban and the rural, the developed and the underdeveloped. But one way to measure the effects on the Black Sea region, which is naturally a transit node of the world, is to look at how maritime traffic has evolved during the pandemic, considering the regional specific characteristics. This way, it becomes easier to define the region’s vulnerabilities dependent on the global trends.

Transportation and shipping have dropped as international trade in goods and tourism has slowed down. While cruises have been halted pretty much everywhere, including in the Black Sea during the first half of 2020, the container shipping has seen an unprecedented decline. According to industry analysts[1], in mid-May, at global level, the idle container fleet stood at around 11% in capacity terms, while containership charter rates were down by around 30% since the beginning of the year.

In the Black Sea, Istanbul is the major container port, handling 60% of all volumes. Constanta (a 12% share) and Novorossiysk (with 8% share) are the two other main ones, with Poti, Odessa and Varna each making smaller contributions. Novorossiysk, Odessa and Varna are mostly serving local markets, while other ports, like Poti, even if small, have also developed their transit capacity. While Istanbul remains the main transhipment port for the Black Sea region, transhipment volumes are moving between Constanta, Istanbul, with both ports enjoying necessary capabilities to accomodate large vessels coming from Asia and elsewhere. Constanta also acts as the point of entry for transit cargo by barge on the Danube River to the Central European countries.

The idea that transportation in the Black Sea could only grow, also supported by the New Belt and Road Initiative promoted by China, made the case for investment in developing port facilities. Ukraine, Bulgaria and Georgia have undergoing expansion plans of their ports started before 2010 and aiming to increase terminal capabilities so that they could accommodate larger ships[2]. All these aims, in theory to the growing transhipment business that would make of the Black Sea a maritime hub.

Transhipment is however volatile and highly price sensitive. Port tariffs are dependent on both economic and security risks and therefore there’s a lot of interdependence between geopolitics and maritime shipping. A factor that has influenced the container business in the Black Sea has been the war in eastern Ukraine. Odessa was initially badly affected, seeing volumes drop by 26% between 2014 and 2015. However, by 2017 these had recovered to pre-war levels and grew strongly by 15% in 2018, due to the fragile cease fire holding.

The global financial crisis of 2008 has caused a slowdown in maritime container trade. However, the overal dynamic did not change significantly, because almost all ports have been focused on their captive market. Recovery from the financial crisis has started, globally, two years later, in 2019, but the seaborne trade growth rate remained modest, considering the ongoing socio-economic problems of the world’s consumer markets: the U.S. and Europe. The U.S. – China trade war and the prospect for a recession, announced in 2019, has anticipated a decrease in shipments worldwide.

The corona crisis delayed some shipments and halted others. Considering the impact of the pandemic in what regards the maritime cargo shipments is already estimated to outpace the decrease in 2008 and 2009 by about 10%, the most optimist analysts see the industry recovering beginning the last quarter of 2021, while the most pessimistic speak of at least three years before the sector goes back to positive values. In the case of the Black Sea ports and shipping industry, it remains to be seen whether the already traditional feature of being captive to local markets will save it again. In the same time, it is likely that investments having been done to accommodate more traffic will not only stop, but will likely bring losses instead of hoped profits.

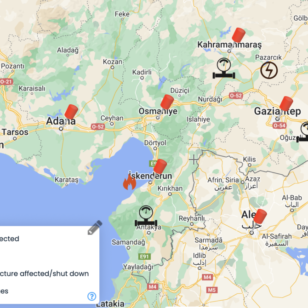

In order to understand how traffic will be affected – and define what new patterns will appear in the Black Sea trade flows, understanding dependencies between individual markets and how these will evolve past the current sanitary crisis is key. It is visible that traffic is lower than usually, by just looking at the map. But we do not know how national and regional consumption of imports will evolve after the corona crisis is over. However, we do know recession will probably hit the world after lockdown policies are no longer in place, even if it is yet early to know the slowdown values, which makes it hard to establish the potential for negative effects that the economic downturns will have on society. Only when we have that we can measure national and international resilience.

The economic data will allow us better understand how society will evolve, at community and national level. However, considering recent history, as well as the patterns evolving from the time pivots described above, we can conclude on the most important topics to be tackled after the corona crisis ends, in the Black Sea area and considering its specific features of connectivity and security. It is likely that the maritime traffic in the Black Sea waters will not grow fast – considering the most optimistic global forecasts and the data we have on the region, it is likely that traffic will go to 2017 levels in two years, if Russia and China continues to ship similar quantities to Europe – this will happen if European consumption will get back to levels prior to the pandemic in less than two years. In the same time, economic and political stability needs to remain constant for that to happen, as they are ultimately the main drivers in the region, even if they’re both influenced by global trade and investment fluctuations.

The post-pandemic questions

The evolution of the global trade flows depends on the economics of the U.S., which is the global biggest consumer and that of the European Union, the market union in the world. Both China and Russia depend on how fast the two consumers will recover from the corona crisis. Both have undergoing reforms which aim at restructuring their economy and both Beijing and Moscow have to manage the socio-economic disparities between their regions, while maintaining stability. All four “meet” in the Black Sea area. All have special relations with Turkey, except China who has worked for better relations as recently as 2019 when China’s central bank reportedly transferred $1 billion to Turkey as part of a currency swap, giving a short-term boost to the country’s dwindling foreign exchange reserves.

With the economic recession coming next the sanitary crisis, Turkey will find itself in trouble again. This has been however anticipated by the current regime in Ankara, who has been touting its neo-ottoman policies in an attempt to gain the public support for Erdogan’s expansionist dreams and have the electorate focused on the external opportunities Turkey has and not its internal challenges.

Turkey signaled since 2019 that it no longer feels satisfied with its “Western ally” status – it seeks to grow its influence in the Middle East and the Balkans and has been negotiating directly over the migration crisis, reaching out to Germany. The political game Turkey is playing poses new risks and asks for the EU position on trade and security matters both. As Turkey resets its relationship with the West (the Western Europe and the U.S. both), it is the Balkans and Eastern Europe – the Black Sea region, that will feel the growing tension.

Russia, on the other hand, saw its economy threatened by the low price of oil in the first half of 2020 and doesn’t have hope for it to grow much higher even after the lockdown is ended everywhere in the world. The Kremlin first needs to keep the country together, and therefore its first priority is making sure economic policies are implemented for the society to remain stable. Second, it needs to keep the buffer zones – whether it becomes more aggressive or not, depending on how things evolve both in the neighborhood and at home, Belarus and Eastern Ukraine are key for making sure the country’s strategic interests are being secured. However, it will have less money to spend abroad and therefore, while some of its influence operations may increase in aggressiveness, others will dilute, depending on where interests lay first. Moscow may choose to spend more money on Ukraine and less on Moldova, for instance.

Russia will correlate its actions to those of the West – it needs to. The U.S. will remain engaged in Eastern Europe and continue to support the regional cooperation between its allies, Poland and Romania. However, due to its internal problems it is likely to keep costs and involvement to the minimum. While defense capabilities will remain in place and the support for the new Intermarium will continue, it remains to be seen how the U.S. relationship with the Western European countries, not willing to contribute “on equal footing” with Washington to NATO, will change. While this will not affect defense alliances in the Black Sea region, it will likely shape the security arrangements in the region.

Security, unlike defense, refers to social resilience to outside influence and the risk that such influence poses. Depending on how the EU solves its socio-economic problems, and whether or not Brussels increases its political power after the sanitary crisis, countries in the Black Sea region will seek to grow or not their reliance on the EU or become more protective against Brussels. With nationalism growing everywhere in Europe, it is still to be seen how the EU member states will work together, under the EU umbrella. As the multiannual financial framework is being discussed, the EU will either focus on building its core, the eurozone while leaving the existing differences between regions deepen or, on the contrary, support a sustainable approach to diminish such differences.

For Romania and Bulgaria – the Eastern European member states bordering the Black Sea, the challenges after the sanitary crisis ends refers to solving their economic problems while also limiting influences from Russia and Turkey to affect continental stability. In essence, as the EU gateway to Asia and the Middle East, the two countries will need to manage traffic and trade towards and outside the EU common market. Considering the negotiations over a more political EU, which involves more coordination for managing funds available, which could imply the potential for fiscal cooperation, the need arises for an extended Schengen zone that would include Romania and Bulgaria.

With less maritime cargo in the ports, but increasing risks, considering the economic challenges that China, but also Russia and Turkey face, the EU will likely need to expand its control over borders, if it truly wishes more coordination and building up the “European sovereignty”. The trade flows from the Black Sea will never be comparable to those from the Northern Sea or the Atlantic – the Western Europe has now little to fear when it comes to competition, considering the limited and decreasing power China has to invest into building its new Belt and Road Initiative. However, considering the need for securing the critical infrastructure – of which that of the cyber space is key, working to integrate digital economy with digital security may force coordination on the very border of the Black Sea border. In the same time, considering the purpose for establishing new green standards for the economy, it may be worthwhile to consider investing into better management of naval traffic, which currently serves Central Europe through the Danube, starting in Constanta.

All these will likely become topics of negotiations in Brussels. With the plan for “repairing and fixing” the EU for the next generation, the consideration of potential risks for the very existence of the EU remains key. That stands into how much the economy is hit and how much of it is dependent on action being taken of outside players, considering the global supply chain which has grown investments, including into maritime infrastructure. For the Black Sea area, the future of the U.S. and the future of the EU are fundamental. But of them, how the EU evolves will determine the fate of this region. If the EU increases its role through further integration, its bordering and neighboring countries will gravitate around it. Even if frozen conflicts will continue to exist, the security environment will remain relatively stable as the large common European market will continue functioning. If, on the contrary, the EU will dilute, as regional differences will deepen and nationalism will continue growing, the Black Sea region will increasingly become unstable, as the potential for conflicts increases.

—

[1] Jaques B., Crisis to cause unprecedented decline in container traffic: Clarksons, May 29, 2020, https://www.seatrade-maritime.com/containers/crisis-cause-unprecedented-decline-container-traffic-clarksons

[2] A presentation of Drewery Maritime Advisors (similar to other industry presentations) shows the case for which the Black Sea ports need to expand their capacity and capabilities to accomodate increased traffic in 2017 – 2020 https://www.espo.be/media/30052013-0830-vanaale.pdf – such increase in traffic never followed, as the economic recovery has been slow worldwide