In the dictionary, “health” is defined as “the state of being well” of the human body. The World Health Organization (WHO) says “health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. Moreover, one of core the principles at the basis of the Constitution of WHO lays down that the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being. Healthcare refers directly and influences the development of human resources. It is one critical infrastructure for the national (and global) development.

- Status Quo in Europe

While it assumes the absence of illness, health is not the absence of disease. However, as we took a closer look at the European healthcare systems, we observed that most of them are disease centred. During the last two decades, European healthcare systems have significantly improved, placing the citizen at the core. However, the inequalities are widening, not only across countries, but also across population groups within each country, costs in healthcare are rising, morbidity associated with an ageing population is increasing, health risks factors such as obesity, alcohol consumption and smoking are more and more linked with disease chronicity.

Public health and the development of healthcare services is said to be a top priority for the policy-makers, no matter the political colour of governments. In the European Union, policy-making is done both at the national and at the Union level. To understand the European healthcare system, we first considered understanding the EU level framework, taking into account the fact that the EU offers the integration model that should be working for comparative analysis between Member States.

The EU proposes health policies that serve to complement national policies and puts together “health strategies” or “action plans”. Moreover, the Council gives guidelines to Member States to follow in terms of health. In the process of adopting a new legislation in the sector of health, or presenting a plan or a strategy, the EU institutions are working together with Member States, Interest Groups and other relevant actors, the “strategic health issues” that are emerging. The EU supports efforts of the Member States to protect and improve the health of their citizens. This is done by several means: the EU may propose legislation and coordinate the exchange of best practices between stakeholders at the EU level, but, most importantly, the EU may provide financial support to support its aims. Therefore, funding for improving the healthcare system is an important component not only at the national level but also at the EU level.

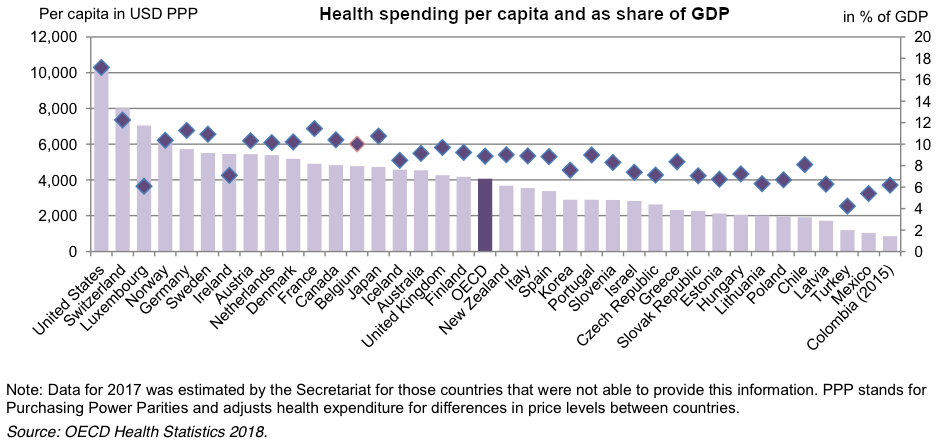

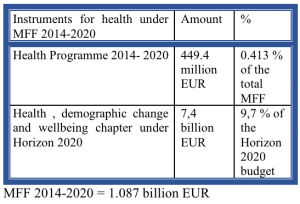

Healthcare funding is, in theory, synced with human resources needs at the EU level. While a priority, it should be linked to the societal and economic challenges the EU is facing. In reality, the EU health spending appears to be minimal. The health budget has been shared between the EU Research Framework Programmes: FP7, Horizon 2020; and, since 2003, the Health Programme. The EU lists the European Fund for Strategic investments and the EU cohesion policy instruments as additional instruments for health support at the Union’s level.

The FP7 and Horizon 2020 have succeeded supporting the research community to conduct excellent research on monitoring health status, but they have not funded breakthrough innovations with tangible results so far. There were new programs and platforms aiming at preventing and eradicating Ebola along with research on neurodegenerative diseases as well as the establishment of eHealth platforms and some research on biotechnology that Horizon 2020 and FP7 funded.

According to the mid-term evaluation of the 3rd Health Program considerable achievements have been made so far, as: establishment of 24 European Reference Networks, support for increased capacity-building to respond to outbreaks, exchanges of good practice in areas as cancer screening, alcohol reduction, HIV/AIDS and TB prevention, but also enhanced support for EU health legislation on medicinal products and medical devices, cross-border healthcare, the eHealth Network activities and Health Technology Assessment.

There were smaller amounts of money, however spent on improving the early screening and prevention. According to the most recent Eurobarometer survey there is still an unequal access to health services throughout EU, an inadequate primary care system, 80% of the healthcare costs are linked with non-communicable diseases and re-admissions, services are fragmented, prevention accounts only, on average, 3% of the total spending of health budgets. While most of the Member States have disease centred healthcare systems – that don’t put an emphasis on the prevention dimension of the health, the EU begins to recognize the value added of the person centred systems. More, as the EU is an integrated market for goods and strives to become an integrated market for services, Brussels advocates for better integration at all levels, including that of the health systems.

2. What next?

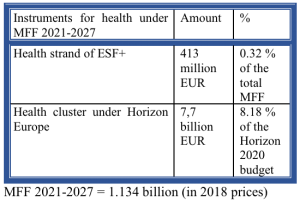

The discussion on funding becomes even more relevant as the EU is considering its budgetary priorities for 2021-2027. A few months ago, the Commission presented the proposals for the instruments under Multiannual Financial Framework post 2020. The concept ‘health in all policies’ is emphasized in some of the instruments. A notable mention is the Health Cluster, under Horizon Europe instrument. Investing in health through Pillar 2 and Health cluster translates into continued support for research and innovation, which translates into investing long term for bettering the European citizens daily lives.

Another instrument that should be the core instrument for health in the EU is the Health Programme. However, studying the proposals, it appears that health is no longer a sine qua non priority for the Cabinet Junker, but it is a chapter under the umbrella of the European Social Fund+ (together with the European Social Fund and the Youth Employment Initiative; the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived; the Employment and Social Innovation Programme). This is an important shift. From a funding perspective, it means that the health sector is no longer a priority. Instead, it is regarded as a complementary component for major elements that constitute social stability: lowering youth unemployment and making sure there’s social assistance for the ones needing it.

The current Commission proposal no longer has healthcare as part of the EU critical infrastructure. In regarding it as a complementary element to other instruments, the Commission places less importance to the status of the wellbeing of the EU citizens, leaving it to the Member States alone to deal with – and compete for funding and ways to support such development. Such a move indicates not only that the Commission has accepted Member States political differences and their limitation in adapting to an integrated paradigm for healthcare – but also that it slowly becomes a passive actor in aiming to shape policymaking supporting further integration.

If, indeed, the Commission’s proposals is to effectively be implemented as it is, it will translate into a cut of the EU health budget – even if the total amount of the MFF is increased, the share for health remains minimal. At first view, this comes counter to what the public opinion wants. According to the last Eurobarometer conducted by the European Commission, 70% of Europeans want the EU to do more for health. But, ultimately, the European Commission is not responding to the EU citizens directly. Member States do. The Commission has always criticized nationalism on the rise – as it causes it losing power. But, effectively replacing healthcare from being critical to the EU integration, it looks like the Commission gives in to nationalism itself, listening not to the Eurobarometer polls, but to the national politics.

Through its proposal for the 2021-2027 budget, the Commission is effectively saying that the European demographics are no longer a priority for Brussels. The European demographics are fully back on the Member States national ’ agendas. But differences between the ways in which Member States will address health will influence the EU and its future. Borders may still be in place, but boundaries between countries have diminished to non-existent – especially in the Schengen area. Still, the health sector is fragmented and providing access to health is unequal for citizens. The ageing population is a common problem for the West and the East – and it encompasses other policy areas, such as migration or the refugee crisis related policies.

The lack of proper prevention or inadequately addressing health risks, the lack of addressing chronic or infectious diseases, and the risks of transboundary diseases pose challenges to the entire European population. With Brussels less active in the health sector and the growing inclination of the Member States to adopt populist policies, the Union will likely see more competition and less integration, less coordination in what regards European social policies.

In our Health Geopolitics, this shift will be a key element that we will monitor and analyze further. Feel free to share this article with your colleagues and friends.