A short discussion on regional energy security and the Balkan, considering the EU’s relationship towards the Three Seas Initiative

This is part of a larger chapter I initially wrote for an academic, co-authored book yet to be published. The original draft is dated August 2018 and deals mostly with the EU neighborhood policy, while also discussing the Three Seas Initiative. The Bucharest Summit hosts the EU Commission President – so the text below may be updated in nuance, if the EU decides to fully support the Initiative.

In the joint statement issued on August 2016 by the 12 signatory member states it is mentioned that they agreed on “facilitating cooperation” for infrastructural and economic development, focusing on energy diversification and improved transportation links. The official document is underlining the importance of North-South connectivity, taking into account the end goal of “completing the European single market”[1].

The European Commission hasn’t said it supported or not the Initiative – even if the signatories also count on EU funding to transform infrastructure projects into reality. Instead, one of the scenarios put together by the Commission in its white paper on the “Future of Europe” in 2017 refers to a state where member states “who want more, do more”[2]. It says that “coalitions of the willing” may arise and work in particular domains, to serve particular goals. This scenario resembles the way the French president recently said he sees Europe evolving in the future: three circles, with the broadest that encompasses countries beyond the 27 member states and the “core circle will be the heart of Europe, with a common currency and a much more integrated labor market, as well as real social cohesion” [3]. Which may translate Brussels silence on the Three Seas Initiative as tacit acceptance. After all, the Initiative can be seen as an example of such a coalition of the willing. But it remains to be seen whether tacitly supporting it equals with preventing the EU from splintering into different tiers.

Active, official support for an independent purely CEE-focused project would mean the EU is supporting it financially and organizationally. Those supporting this scenario, say that the EU would not only strengthen it, but its support would also reduce the likelihood that the Three Seas Initiative becomes politicized. EU backing would reduce the influence of individual countries in the region. Right now, it is an unofficial declaration with no binding legal structures in place. The project is supported by the U.S., which has an interest in keeping the containment line and the alliance in Eastern Europe, from the Baltic to the Black Sea effectively functioning. But the U.S. doesn’t fund anything related to the project – its political support may bring it to the attention of American investors. Companies, however, are deciding on whether to invest or not, based on assessing risks and opportunities relating to particular businesses. Not their country’s policies. This is why countries in Central and Eastern Europe welcome the U.S. support, but would love the EU’s.

The EU needs to consider however, the implications of the Three Seas Initiative for the projects it has approved already for the region and, not the least, the Initiative’s impact on the Balkans fragile politics. Being heavily supported by Croatia, intensifying infrastructure that connects it to the North of Europe, makes Serbia – and the other non-EU member states in the Western Balkans, wonder about the EU’s intentions of helping create a balanced, stable neighborhood. Therefore, while the EU would be gaining on more infrastructure, Brussels would be seen to favor Croatia’s proposals over those of other countries in the region, some that the EU has already accepted to fund. For the European diplomacy to work best in the Balkans, it is perhaps better for the Three Seas Initiative to stay as it is – mostly funded by the participating states themselves, with little private investment.

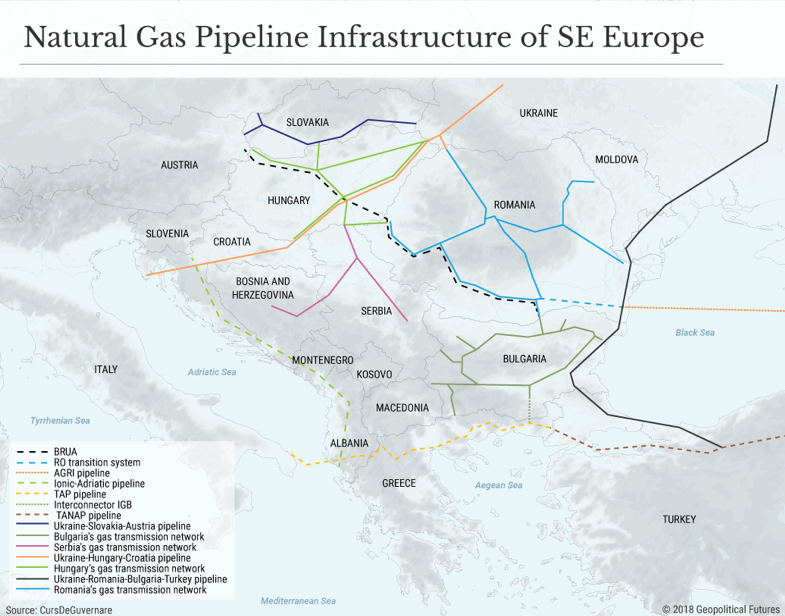

More, considering the energy union goals and because energy infrastructure in the region is still scarce, the EU has been actively investing in interconnecting the energy transmission systems in the region. The EU already allowed funding and supports the so-called “projects for common interest”[4] which are aimed at making use of existing infrastructure and available as well as potential European energy resources in order to increase both energy security and energy efficiency for the EU. Among these, there is the Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria (BRUA) pipeline, connecting the gas transmission system of the four countries while creating the infrastructure for transporting gas from the Black Sea to the European markets.

The EU also supports the construction of the Krk LNG terminal in Croatia and the expansion of the Świnoujście. One of the two major concrete projects that have been talked about within the Three Seas Initiative is the liquid natural gas (LNG) infrastructure: the terminals in Poland and Croatia. The same that the EU supports. There is presently one operational LNG terminal in Poland and a second terminal was planned to be completed in Croatia in 2019 and start operations in 2020. What the Three Seas Initiative adds to the LNG terminals projects is the proposal for building up distribution pipelines that would connect the two, aiming to provide an alternative energy source to Russian gas.

Some of the gas to be pumped in would actually be American gas, considering the U.S. currently has export capabilities. This also supports the strategic interests Washington has in the region, considering the ‘new’ Intermarium[5] alliance formation into a new containment line in Eastern Europe. However, not all projects that would be proposed for connecting the North to the South of the Eastern European region are economically viable and complement those already supported by the EU. Some may even compete against them. Considering this, the EU interests don’t necessarily fully overlap those stated by countries signing the Three Seas Initiative. Which is why the EU can’t officially endorse the proposal and can only keep silence over the matter, for now.

The other major concrete project relates to transportation infrastructure. Called Via Carpathia, the project consists of a highway that will stretch from the Lithuanian seaport Klaipeda to the Greek port of Thessaloniki on the Aegean coast. The region has little transportation infrastructure connecting the north to the south – and in particular, connecting the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, where NATO and American troops are currently stationed. Most of the infrastructure developed in the Central and Eastern European region has been supporting east-west connectivity, a result of the German economic dominance, considering the regional dependence on trading with Germany.

The Three Seas Initiative is more geopolitical rather than economic at this point. It relates to securing a way for the countries in the region to integrate with one another and not necessarily with Western Europe. But, in stretching from the Baltic and the Black Sea into the Adriatic, it intersects with the problems of the Western Balkans, a historical European challenge. With efforts being made by Brussels to support the development of the region, it can’t risk for countries like Serbia or Bosnia Herzegovina, that haven’t yet gone past the scars the war in the early 90s have posed, to feel isolated.

In the same time, Brussels policy towards the Western Balkans is not much changed. And, even if progress has been made on the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue, in practice, energy infrastructure and trading still lags behind. Restructuring and reformation are still pending. This is an area where the EU can help the region – and one where the Three Seas Initiative will not necessarily help.

[1] Joint Statement on the Three Seas Initiative, http://predsjednica.hr/files/The%20Joint%20Statement%20on%20The%20Three%20Seas%20Initiative%281%29.pdf, accessed Aug. 7, 2018

[2] Those who want more, do More, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/enhanced-cooperation-factsheet-tallinn_en.pdf, accessed Aug. 7, 2018

[3] Emmanuel Macron sees the future of Europe in three circles, http://www.economicsherald.com/emmanuel-macron-sees-the-future-europe-in-three-circles/, July 31, 2018, accessed Aug. 9, 2018

[4] The list of the projects of common interest (PCIs) by country, https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/documents/memberstatespci_list_2017.pdf, November 2017, accessed Aug. 9, 2019

[5] The Intermarium was originally a plan pursued after World War I by Polish leader Józef Piłsudski that wanted to lead a federation of Central and Eastern European countries, meant to protect them from the influence and potential aggression of the Russian empire. The term has been revived by the appearance of the strategic partnership between Poland and Romania, supported by the U.S. and which has a similar goal: essentially form a “cordon sanitaire” and be able to protect the region against potential Russian aggression. Past 2014, it is considered that NATO’s support for the initiative has transformed it into the West new “containment line” against Russia.